The Dewdney Trail

Historical Name: Dewdney Trail

Common Name: Dewdney Trail

Location: Passes through the south east corner of Rossland

Date of Construction: 1865

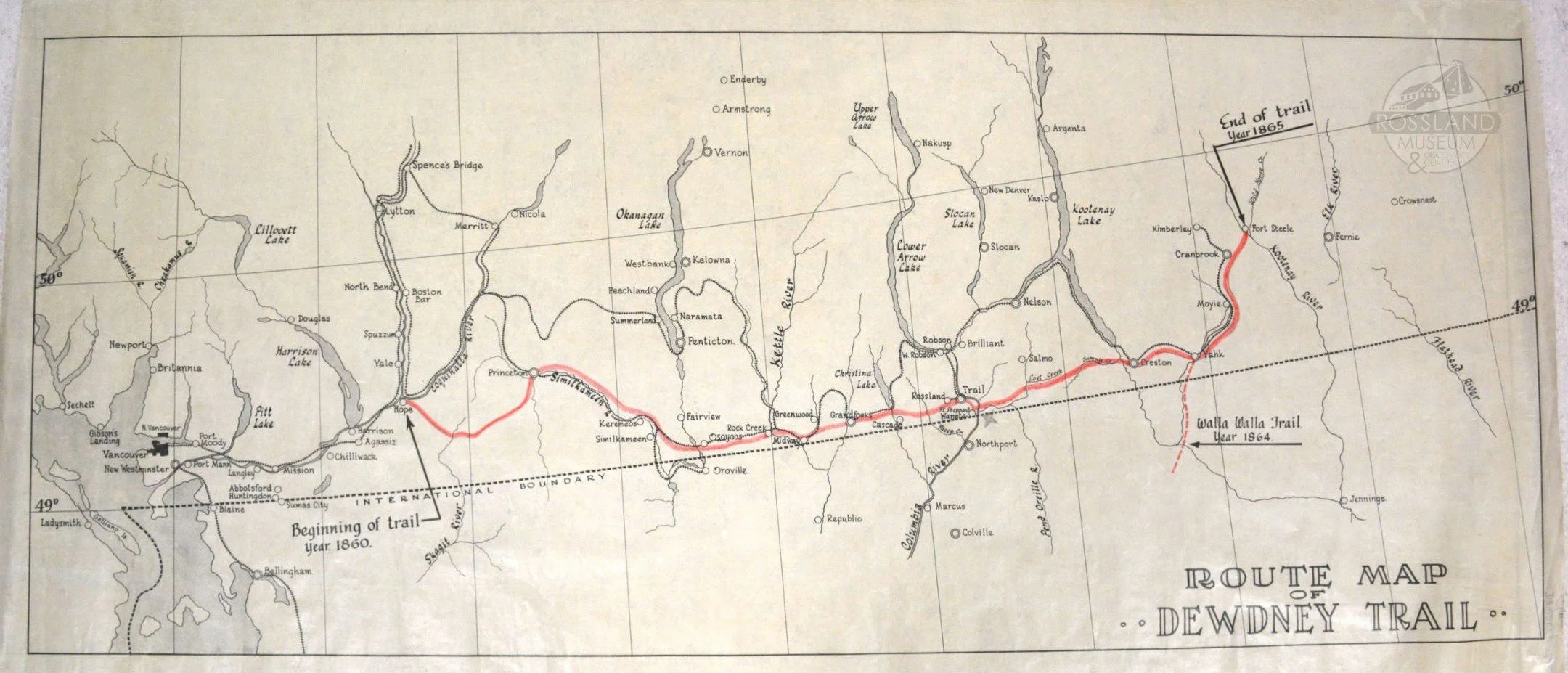

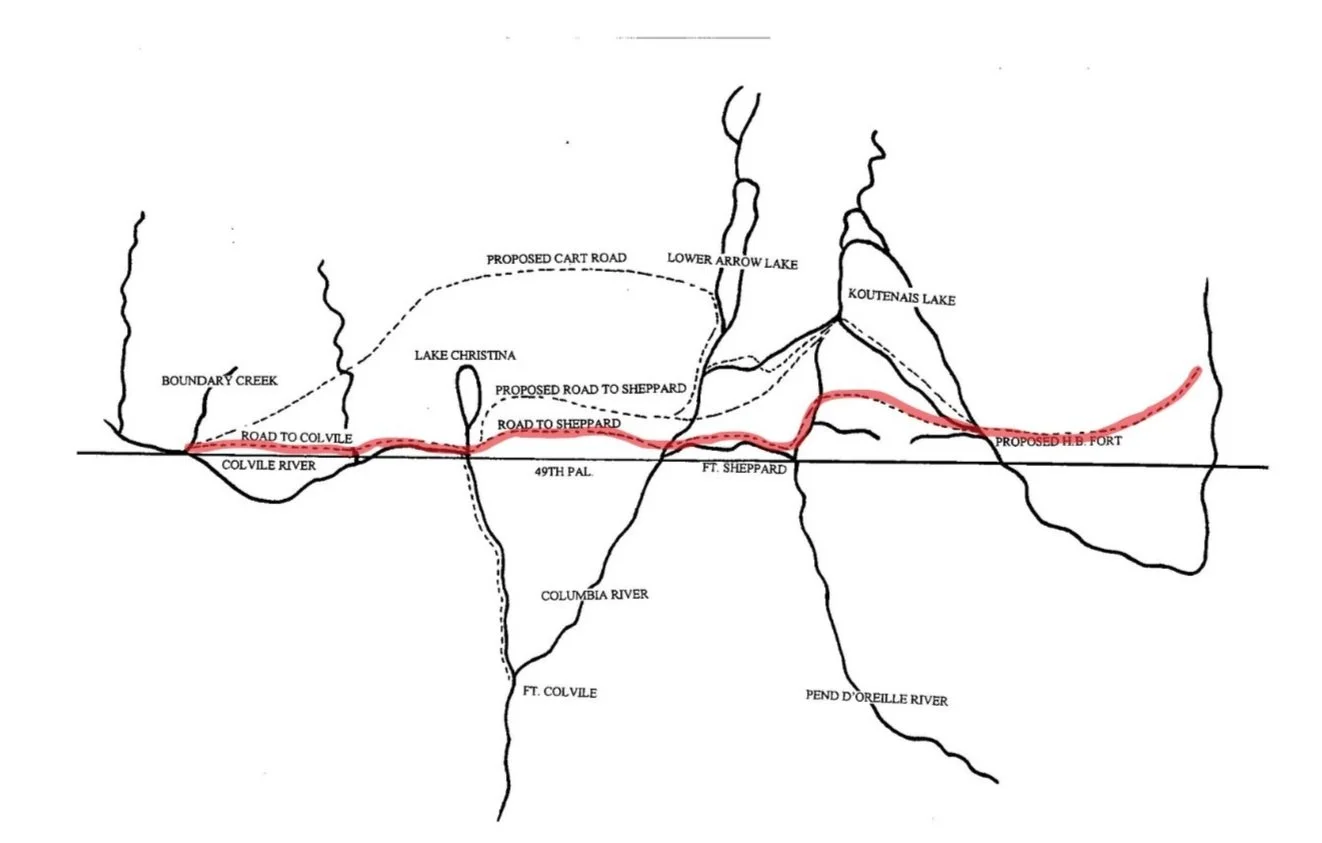

Route Map of the Dewdney Trail. Rossland Museum Collection.

The Dewdney Trail was a 720-kilometre-long trail that spanned the majority of BC, reaching from Hope, on the Fraser River, to Wild Horse Creek in the East Kootenays. The Trail was made up of two main segments. The first segment – from Hope to Rock Creek – was constructed in 1861 in response to the Rock Creek gold rush. The second segment extended the trail to Fort Steele, in response to the 1864 gold rush at Wild Horse Creek. After the completion of the trail, both gold rushes died down, but the Dewdney Trail found a new life in the 20th century, guiding railroad and highway construction along its length. The Dewdney Trail was named after the lead engineer who worked on the project, Edgar Dewdney.

Although Edgar Dewdney is often credited as the sole individual responsible for the completion of the Dewdney Trail, the entirety of the process – from finding the route to grading the trail – relied on the knowledge and labour of Indigenous and Chinese peoples. Dewdney followed prior-laid paths wherever possible, particularly in the Rock Creek to Fort Steele section of the trail. He often ended up following trails used and maintained by local Sinixt, Ktunaxa, and other Indigenous people or retracing the steps of past explorers such as John Palliser – who had also depended on Indigenous guides’ knowledge of the land. Consequently, Dewdney’s trail was closely intertwined with the local knowledge and histories of the region’s Indigenous peoples. Thus, just as Dewdney’s efforts were pivotal in opening a pathway to the interior of British Columbia, the Indigenous and Chinese workers who worked alongside him played an instrumental role in the exploration and development of southeastern B.C.

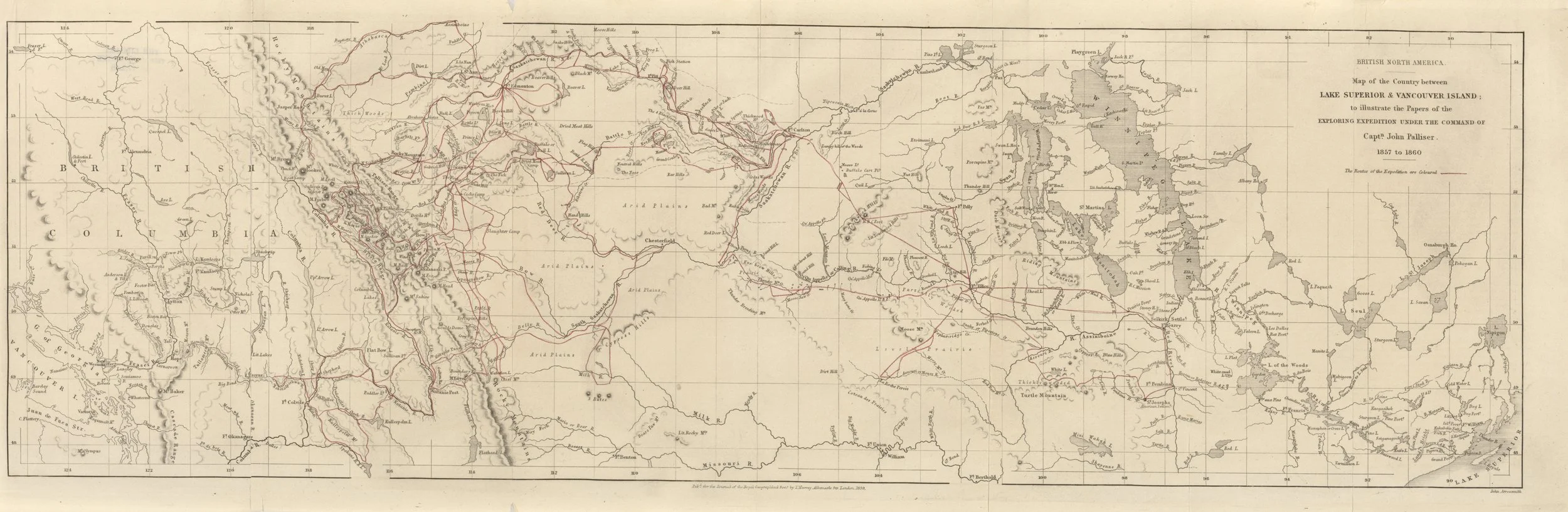

Map of Palliser Expedition. Courtesy of The University of Texas PCL Map Collection

The First Stretch: Hope to Rock Creek

In the late 1850s, gold was first discovered in the interior of British Columbia near where the Pend d’Oreille and Columbia Rivers meet. News spread, and the area was quickly filled with prospectors. Many of these prospectors were Americans, and due to the proximity of the US/BC border – which had only just been established at the 49th parallel by the Oregon Treaty of 1846 – they were bringing in most of their supplies from the States. To assert control over the area and allow the money from the gold boom to reach British coffers, Governor James Douglas ordered that a trail be built to help bring British supplies over to Rock Creek and bring Rock Creek’s gold back to the west coast of BC. Thus, in 1860, the construction of the Dewdney Trail began; by late 1861, the trail had reached the epicenter of the then-current gold boom: Rock Creek.

Surveying the Route

The route for the first part of the trail, which would link the Fraser Canyon mining camp to the Rock Creek camp, was surveyed by the Royal Engineers under the direction of Governor Douglas. By the middle of 1860, the route had been decided: starting at Hope, the 400 km trail would follow a path that the explorer Alexander Anderson had surveyed in 1846. Through the guidance of a local Indigenous man known as “Black-Eye,” Anderson was able to find a route that went northeast from Hope, bypassing Hope Mountain and following Indigenous trails and passes to a small town named Tulameen. From Tulameen the trail branched out, with one path going north to Kamloops and the other south to Princeton. The Royal Engineers began their trail by following Anderson’s path from Hope to Princeton; then southwards past Keremeos and to Osoyoos Lake. From the lake, the Royal Engineers followed an old wagon trail due east to Rock Creek. With the route decided and construction on the horizon, the contract for the trail’s creation was given to a young civil engineer by the name of Edgar Dewdney.

Constructing the Trail

Starting in the middle of 1860, Dewdney and his team of Royal Engineers started pushing the trail the 100 or so kilometres to Princeton. In the late summer, Dewdney began to have disagreements with his team over the best route forward and subsequently abandoned the project, leaving the Royal Engineers to complete the Hope to Princeton portion of the trail. Once there, the trail’s construction was halted until the next spring. In the spring of 1861, Dewdney and a new partner, Walter Moberly, restarted construction. Leaving the Royal Engineers behind, Dewdney and Moberly found workers by hiring settlers from Hope and the surrounding areas. Dewdney and Moberly, along with their team of settlers, worked quickly, pushing the trail to Keremeos in short order. From Keremeos to Osoyoos, Dewdney veered from the original path surveyed by the Royal Engineers, and the trail dipped south across the border into Oroville, Washington. A few months after the trail had been completed, a group of Chinese miners were robbed near Oroville and the trail was rerouted to avoid this area. A group of Chinese men pioneered a new route through Richter Pass, leading to the creation of the aptly-named “Chinese Trail,” and bringing Dewdney’s trail fully into British territory. After their excursion to the States, Dewdney and Moberly got the trail to Osoyoos and over Anarchist Mountain, and completed the first leg of the Dewdney Trail by the end of 1861.

The trail, meant for wagons, horses, and the transportation of cargo, was built under strict conditions; when it was finished, the entire length of the trail was four feet wide and had no slope with more than one foot of rise for every twelve feet of horizontal distance (a grade of 8.33%). Even so, the high number of prospectors travelling on the trail led to its quickly degrading, often thinning to two feet of usable trail, riddled with holes.

Finishing the Trail: Rock Creek to Wild Horse Creek

In 1863, gold was discovered further into the remote southeast of BC at Wild Horse Creek; word of this find quickly spread through the colony, eventually reaching Governor Seymour in Victoria. By the middle of 1864, Seymour had ordered a small police force to Wild Horse Creek with the goal of bringing law and order and collecting customs fees and taxes. Seymour now had to face the bigger problems: transportation and communication with a remote mining camp. Seymour spent some time looking for engineers willing to undertake the project and, after many recommendations, gave the job to Edgar Dewdney in the spring of 1865.

In an 1865 letter from Dewdney’s past partner, Moberly – who was now working as his supervisor – informed Dewdney that he would be responsible for surveying a route and constructing a trail from Rock Creek to Wild Horse Creek. Moberly informed him that for the purpose of his expedition, he would be assigned two assistants, and that “any further assistance that may be absolutely required… will have to be employed on the ground.” This meant that Dewdney would no longer have to work with the Royal Engineers he had clashed with in the past, and was instead free to employ whoever he pleased. Although this new arrangement seemed to free Dewdney from the stricter regulations working with the Royal Engineers implied, it also meant that Dewdney was, more or less, on his own.

Surveying the Route

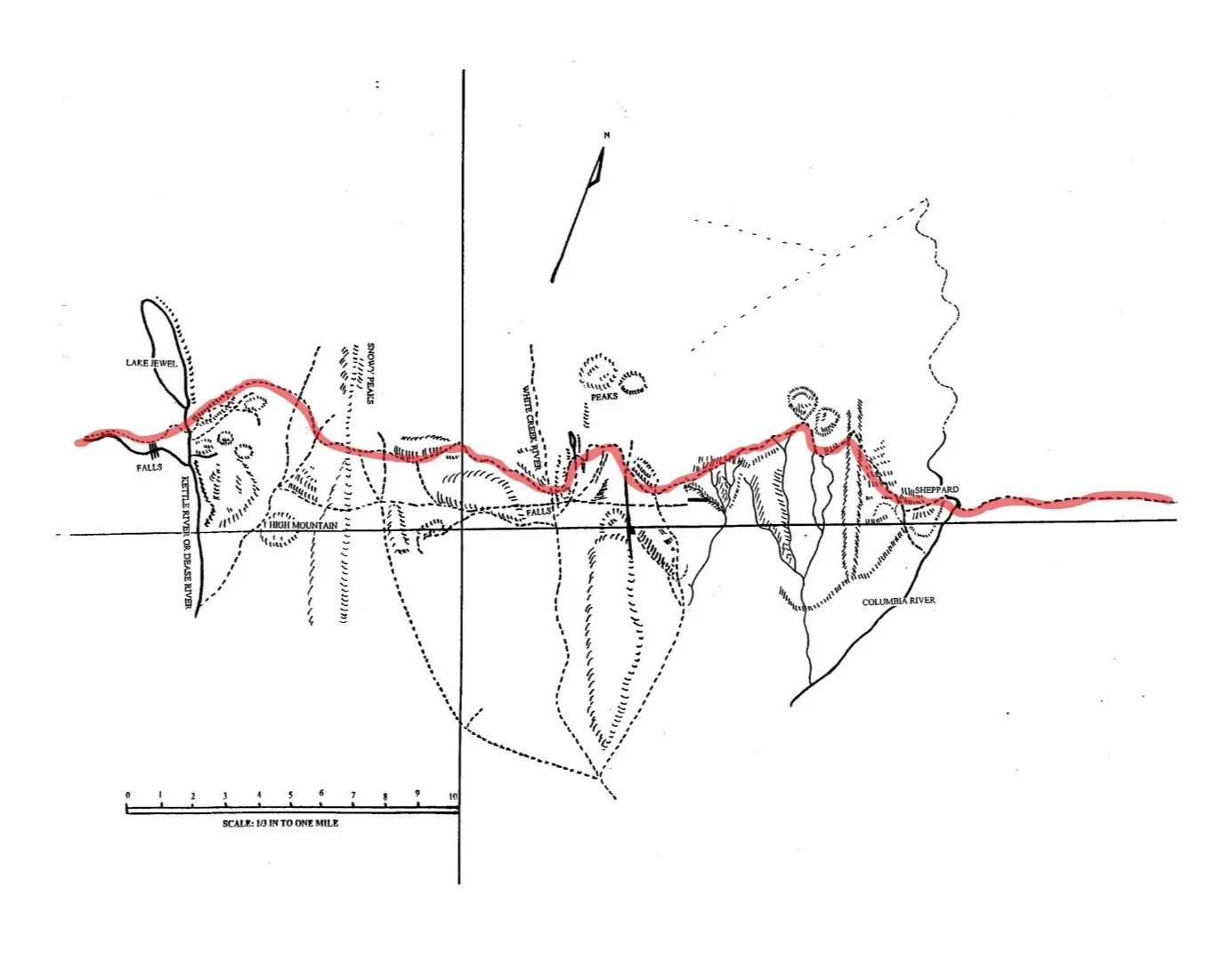

Dewdney’s Notes: Map One (Collage). Courtesy of Boundary Museum Society

In the spring of 1865, Dewdney set off from Hope to begin surveying the route for the trail’s construction. Dewdney estimated that this extension, reaching all the way from Rock Creek to Wild Horse Creek, would span nearly 430 kilometers. Dewdney began his expedition in Colville and followed Boundary Creek north to Jewel Lake. To save time and find the easiest way to Wild Horse Creek, Dewdney followed prior-layed paths wherever possible; he often ended up following trails used and maintained by local Indigenous peoples or retracing the steps of past explorers such as John Palliser. In both of these cases, the route Dewdney followed was closely intertwined with the local knowledge and histories of the region’s Indigenous peoples.

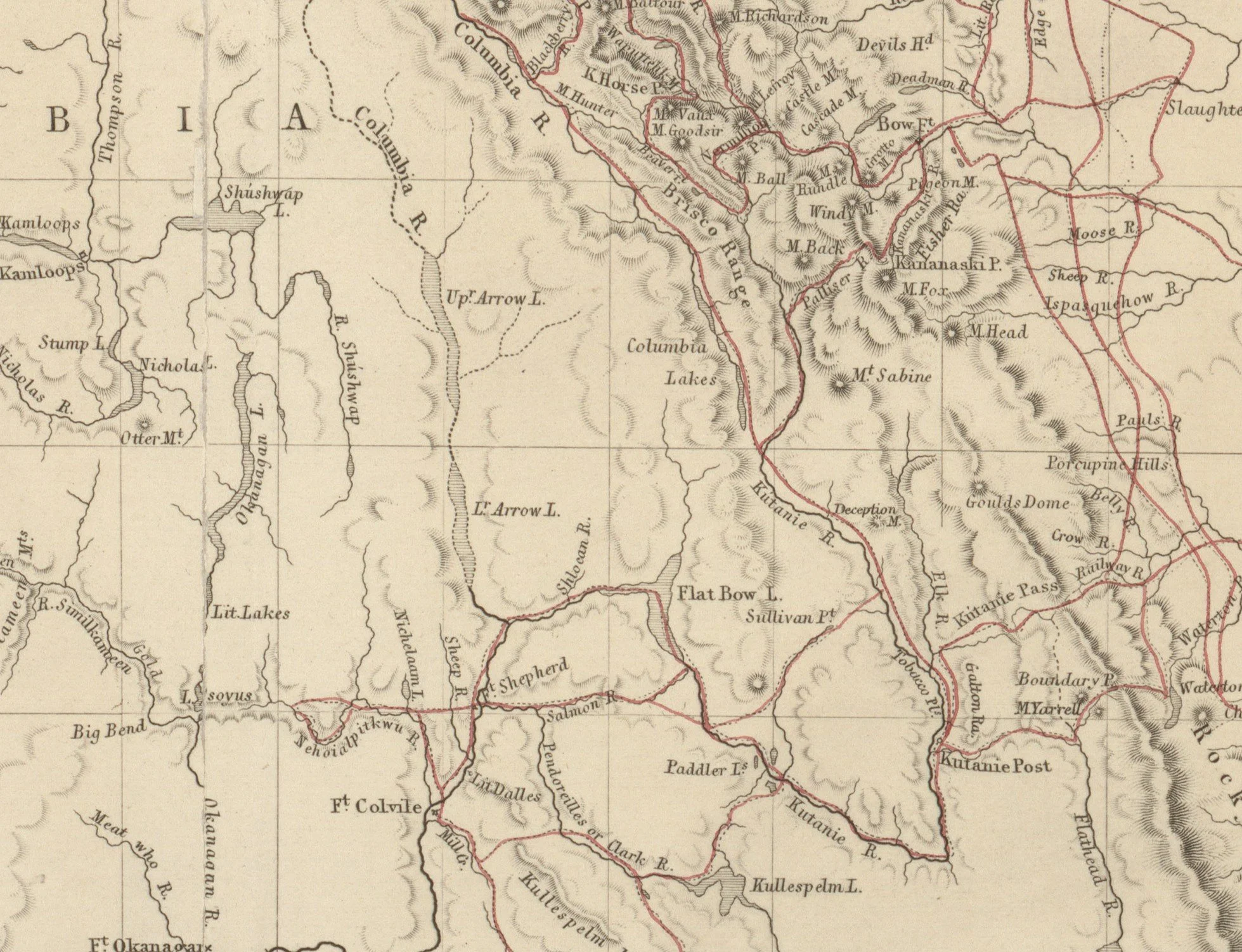

After reaching Jewel Lake, Dewdney worked his way south-east, arriving at what is now Grand Forks and then making his way to Christina Lake. From this point on, Dewdney’s route closely followed trails that Palliser had mapped during the Palliser Expedition (1857-1860). On this expedition, Palliser often employed Indigenous people as guides, relying on their knowledge of the land to find the best way between areas of interest. During his travels along the route that would become the Dewdney Trail, Palliser employed guides from many of the region’s Indigenous peoples. First, to navigate from Fort Shepherd to Kootenay Lake, Palliser engaged three Sinixt guides. Later in the journey, from Kootenay Lake to Columbia Lake, Palliser hired two Ktunaxa people as navigators. The route that Palliser followed with these guides, which he describes in a letter from 1859 as a “practicable trail” from Fort Shepherd to the Kootenay River, is the same route that Dewdney followed two years later. Considering the difficulty of finding practical mountain passes, Palliser’s route, which, according to his 1859 letter, had the advantage of “throwing the whole [route]… into British dominion” and “escaping the ascent of 500 feet” through the Nelson subrange of the Selkirks, was of vital importance to the final route of the Dewdney Trail.

Map of the Palliser Expedition. Courtesy of the University of Texas PCL Map Collection

Following the route Palliser had mapped, Dewdney’s trail was forced north, eventually reaching the southernmost point of Lower Arrow Lake (a route was later found to avoid this northward loop). From Arrow Lake, Dewdney had two ideas for the trail’s route; the first of these two paths followed the edge of Kootenay Lake, which Dewdney followed on canoe, searching for a suitable crossing place. However, Dewdney wasn't able to find any way around the lake, and to instead take a more southerly route, passing around Kootenay Mountain and ending at the base of Kootenay Lake. In finding this route, Dewdney relied heavily on the knowledge of local Indigenous peoples who acted as guides and packers, showing him the ways through the mountains and helping his team carry the necessary food supplies and trail-building tools on their journey.

In an 1896 interview with the Rossland Miner, Dewdney – discussing the labourers he employed for the construction of the trail – states that he had employed a “large force of Indians employed as packers and guides” and that in his early reconnaissance for the trails route he came through “Lower Arrow Lake… with an Indian guide.” Although Dewdney doesn't identify which Indigenous groups these guides belonged to, his guides in the Kootenays were most likely the same Sinixt and Ktunaxa people whom Palliser had employed just years before. After Dewdney had reached the base of Kootenay Lake, the Trail was able to wind its way through the easy mountain passes charted by Palliser, before reaching its end point: a ferry crossing along the Kootenay River, just eight kilometers from Fort Steele.

Dewdney’s Notes: Map Two. Courtesy of the Boundary Museum Society

Constructing the Trail

After the general path for Dewdney’s trail had been surveyed, and in fact before the route was fully flushed out, Dewdney had begun hiring workers for the gruelling tasks ahead. One of the main steps in the construction of the trail was the clearing of trees, fallen logs, or other obstacles (such as boulders and shrubs) that lay along the chosen path. Next, the trail had to be graded – the ground smoothed and the steepness controlled – and widened until it met the criteria laid out for Dewdney: no grade higher than ~8%, and no narrower than four feet. Due to the length and difficult nature of Dewdney’s route, these two steps would take an extreme amount of time, manpower, and money.

By searching townsites such as Fort Hope and Wild Horse Creek and finding prospectors willing to work, Dewdney was able to recruit a sizable workforce – with somewhere between 200 and 300 men in his hire. In particular, Dewdney employed many Chinese men, as they often worked for lower wages and were seen as hard workers. In an 1865 letter discussing the trail building process, Dewdney wrote that he had hired Chinese labourers to carry out grading work, paying them “2.75 per diem” and requiring them to “find their own provisions and tools.” Between these Chinese graders and the two groups of choppers Dewdney also employed, Dewdney had a workforce totalling around 300 men: 200 in chopping and 100 in grading.

In regards to the trail’s early construction, Dewdney stated in an 1896 interview with the Rossland Miner that he had 200 men, “half whites and half Chinese,” who started trailblazing at the Columbia River. Later in the interview, Dewdney said that he split his workforce into two groups. One group was to start “building the trail from the Columbia River east to Wild Horse,” and the other was to work “from the Columbia River west to the connection with the Hope Mountain trail” he had built in 1861. With the size of Dewdney’s labour force, the trail was quickly completed, and the road was constructed within seven months of Dewdney first leaving Fort Hope. Without the labour of these Chinese men Dewdney would have struggled to complete his trail within the seven-month timespan, and he wouldn’t have been able to stay within the budget he had been given by the government.

Rossland and The Dewdney Trail

Although the Rossland gold boom didn't begin until the 1890s – almost 30 years after the Dewdney Trail first passed through the area – the Dewdney Trail still played an important role in Rossland’s history. In the spring of 1890, two prospectors by the name of Joe Moris and Joe Bourgeois came to the Rossland area along the Dewdney Trail. Moris and Bourgeois were not the first prospectors to look around in the region – hundreds of prospectors trickled through the area to try their luck – but they were the first to strike gold. In the summer of 1890, Moris, Bourgeois, and Eugene Topping (an assayer from Nelson) staked five claims on Red Mountain: the War Eagle, the Centre Star, the Idaho, the Virginia, and the Le Roi.

By mid-1891, word of Rossland’s gold had spread and prospectors scrambled into town, either arriving by boat along the Columbia River or hiking the distance along the Dewdney Trail. Once gold had been found, the next obstacle was getting it down from Red Mountain; for this, a crude trail was cut down from the mines to connect up with the Dewdney Trail. From there the Dewdney Trail – recently cleaned up and upgraded by Rossland prospectors – was used to cart the ore to the Columbia River where it could be taken by ship to the south. Two years later, in 1893, a more direct wagon road near the Dewdney Trail was completed and used instead to transport ore to the Columbia River.

After the gold boom had slowed down and new infrastructure had been created, the Dewdney Trail fell to the wayside of Rossland’s history. That is, until 1910, when the construction of the Kettle Valley Railway (KVR) began. With the goal of connecting B.C.'s southern interior with the rest of Canada, the KVR, a subsidiary of Canadian Pacific Railway, built a rail line from Midway to Hope. This rail line followed the route of the Dewdney Trail, which once again played a role in the development of infrastructure in BC’s Interior.

Today, very little of the Dewdney Trail still exists, but its influence can still be felt. The Crowsnest Highway 3, the main highway servicing the interior of BC, follows nearly the same path Dewdney did in 1861 and 1865. Further, the development of the KVR and the existence of the Dewdney Trail impacted Rossland’s settlement patterns, with many Chinese railroad workers and American prospectors settling in the area.

The section of Dewdney Trail between Christina Lake and Rossland remains popular with bikers and hikers alike for its recreational appeal. Around 2.8 kilometres of the trail's original route falls within Rossland’s city limits and is maintained by the Kootenay Columbia Trail Society.

For More Information:

Richie Mann’s Speaker Series presentation at the Rossland Museum

Canada’s Historic Places - Dewdney Trail

Rossland Heritage Commission - Sites (see Dewdney Trail)

Contribute your own memories/experiences of the Dewdney Trail:

The form below will email us your message. If you prefer to speak to us directly or have other questions or comments about this page, please call (250) 362-7722 or email the archives directly at archives @rosslandmuseum.ca