Origins of Skiing: Olaus Jeldness

by Ronald A. Shearer

Topics Covered in this Essay

Olaus Jeldness

Early Years

Rossland

Spokane

A Contemplative Man

The Jeldness Family

Who Was Olaus Jeldness?

Ski Running

Ski Jumping

The Velvet Mine

Jeldness Tea Party

Winter Carnival

Afternote: Mount Jeldness

Acknowledgements

The information presented in this paper has been compiled from many sources: private papers, correspondence and other documents held by archives, mining handbooks, city street directories and historical newspapers. The accuracy of information in newspaper stories is always somewhat suspect, but it represents a large part of what is knowable about Olaus Jeldness. I have tried to be cautious about newspaper stories and in those few cases where it was possible, to check against other sources of information. However, because of my reliance on newspapers, it is inevitable that some errors of fact and interpretation are reported here. Also, there are many gaps in the available information -- gaps that are beyond my research skills to fill -- and the reasons behind many events are obscure. In some of these cases I have offered my speculations about what might have happened or why. I have identified these instances as speculations; they should be treated as nothing more than that. I have also left many questions hanging.

Two technologies made possible the research underlying this paper, one relatively old and the other relatively new. The older technology is microfilm. Many documents and particularly old newspapers that would be otherwise very difficult if not impossible to access are preserved on microfilm and I have made intensive use of several collections. The main depository for microfilms of old British Columbia newspapers is the British Columbia Archives in Victoria, but Selkirk College Library also has a remarkable collection of microfilms of newspapers of the Kootenays. The Vancouver Public Library obtained the microfilms from Selkirk College through inter-library loan and provided the facilities for me to read them. Some issues of the Rossland Miner are missing from the Archives and Selkirk collections. I was able to read these at the British Library's newspaper library at Colindale, London, England. A crucial collection of microfilms of back issues of the Spokesman Reviewat the University of Washington's Suzzallo Libraryproved indispensable in researching Olaus Jeldness' life after he moved to Spokane. I also made important use of microfilmed issues of the Oregonian in the Multnomah County Library, Portland, Oregon. Microfilms of some old Colorado newspapers were obtained through the University of British Columbia Library.

The newer technology is the internet, the resources of which continue to expand. Some of the research reported in this paper would not have been possible without access to the BC Historical newspapers digitized by the UBC library, the Digital Archives of the State of Washington, the Archives of the State of Oregon, the Oregon Digital Newspaper program of the University of Oregon, the Northwest History Database of Washington State University, the Chronicling America project of the Library of Congress, the Utah Digital Newspapers of the University of Utah, Newspaperarchives.com and Googlenewsarchive.com. The Google news archive is particularly valuable because it indexes early Spokane newspapers. Unfortunately, Google has not maintained the service and the search engine has some quirks and serious failings, including assigning incorrect dates to some articles. Moreover, the coverage of the Spokane papers is very incomplete.

Much of my research concerned the Jeldness genealogy. In this regard I have made intensive use of the internet-based genealogical services of Ancestry.com and FirstSearch.com. Indeed, these genealogical services were invaluable. A remarkable book, in Norwegian, by Magne Holten, Amerikafeber (America Fever), documents emigration from the Surnadal region of Norway to North America. With the help of a Norwegian-English dictionary, it has provided evidence that I have been unable to find elsewhere.

More traditional sources, printed works and manuscripts have also been vital. I must thank the Spokane PublicLibraryfor access to theSpokane City Directories; the University of British Columbia Library and the British Library's newspaper library at Colindale, London, for access to old mining books and mining magazines, some of them on microfilm; the British National Archives in London for access to files on long defunct British corporations; Special Collections and Archives of the University of Oregon Knight Library for access to the Jonathan Bourne Papers; and the Spokane County Clerk's Office for access to Olaus Jeldness' probated will. In his book, The Ski Race, Sam Wormington provides a unique and accessible collection of many, but not all, of the relevant clippings from the Rossland Miner. Wormington was a devoted admirer of the Olaus Jeldness of legend.

The Morgan family has a collection of Jeldness papers and photographs that Diana Morgan graciously permitted me to examine. They proved to be invaluable as a source of information about Olaus Jeldness that could not be found elsewhere. Similarly, the Rossland City Archives has a collection of Jeldness papers, donated by the Morgan family and city taxation records that I was permitted to pore over. Both collections have been immensely useful. I am grateful for access to them.

Marcie showed remarkable patience with and understanding of my quirky, compulsive research and writing habits, read the manuscript and graciously corrected some of my egregious grammatical errors.

I am indebted to you all

Of course, all errors in research, interpretation and writing are mine and mine alone.

Vancouver

January, 2013

FOOTNOTES and ENDNOTES

This manuscript has two types of notes. Footnotes, indexed by superscript letters (a, b, .. zzz) contain information that I consider relevant but not of sufficient importance to include in the text. Some footnotes elaborate on a point in the text, others provide context or background. Some footnotes also contain source references. Endnotes, indexed by superscript numerals (1, 2, 3 … 599) contain source references only. They are printed at the end of the manuscript.

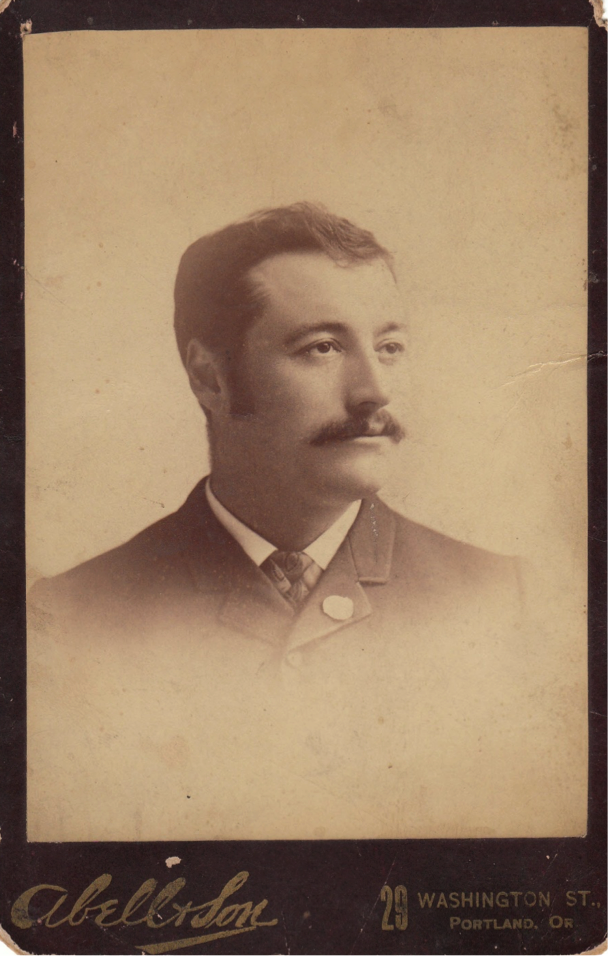

Olaus Jeldness

Olaus Jeldness was a "mining man," but he is a legend in Rossland, British Columbia, not for his accomplishments in mining, but for his exploits on skis. Yet, despite his local fame, surprisingly little is known about his life and some of the details regularly repeated in the extant literature are incorrect. In his adult life, skiing was important, at times a basic means of locomotion in winter, but more generally a relaxing and exhilarating relief from the stresses and anxieties of dangerous and demanding everyday activities. However, at root his life was an odyssey through the mining camps of North America (and some in Europe), in a determined quest for ever elusive riches, always guided by the optimistic belief that the next hole in the ground would deliver the big bonanza. His personal bonanza was found on an isolated mountainside outside Rossland. It gave him a modest personal fortune and for an extended time he led a prosperous life style. However, he died in less than prosperous circumstances, a victim of his own speculative nature and the depression of the 1930s. This paper reports what I have discovered in my attempt to understand Olaus Jeldness and his life.

Olaus Nilsen Jeldness was born Olaus Nilsen Gjeldnes, one of seven children in the family of Nils Gjeldnes on a farm in what was then the rural municipality of Stangvik, Norway, on October 1, 1856.[1] Following administrative reorganizations, Stangvik is now a village in the larger municipality of Sarnadal, in the district of Nordmore, in the county of More og Romsdal.[2] Stangvik is deep in a fiord on the southwest coast of Norway, about 375 kilometres north and somewhat west of Oslo and about 100 kilometres southwest of the famous ski resort of Trondheim. The Gjeldnes family had a farm, with a substantial farmhouse that is still in use. Olaus, like other family members, changed the spelling of his name to Jeldness (or, perhaps the immigration officials changed it for him) when he immigrated to the United States.

I have discovered nothing about his early life in Norway, except that he was an accomplished skier and ski jumper from childhood. Olaus reported that before leaving Norway, he set a national (and by implication, a world) record with a ski jump of 92 feet, a record that he asserted stood until 1888 when it was bested by another Norwegian who jumped 100 feet.[3] I have not been able to verify Olaus' claim; nor could Wormington.[a] However, Olaus had a reputation for honesty and even if it was not recognized as a national record, the jump was a remarkable achievement for the times. By today's standards, these records seem puny. However, it was very early in the history of jumping competitions, skiing equipment was primitive and science had not yet been applied to the refinement of jumping techniques and the design of ski jumps and jumping hills.

Olaus' education is a blank. He left Norway at age 16, but I do not know if he remained in school until his departure. However, given what I know about his subsequent accomplishments, whatever the number of years of formal schooling, I would be surprised if he was not also academically gifted. His letters and a few other writings show a mastery of the English language that, while not perfect, would be the envy of many native speakers. He also proved himself capable of self-directed advanced study in geology and mining engineering and thoughtful explorations in politics, religion and moral philosophy -- all of this while working hard in a variety of mining camps on the western mining frontier of North America. Regardless of his level of formal education, he was a highly intelligent man.

THE EARLY YEARS

San Juan County, Colorado.

Olaus Jeldness immigrated to the United States in May, 1873,[4]when he was 16, to join two older brothers in Michigan and work in the iron mines.[5] Sometime during the following year the three brothers moved on to the lead mines of Missouri. One did not get rich digging in lead mines, but one could get rich prospecting for gold or silver. In the mid-1870s, the Black Hills of Dakota Territory began to attract a horde of gold-crazed prospectors and in 1876 the Jeldness brothers joined the rush.[6]

By treaty, the Black Hills belonged to the Sioux tribe of Native Americans and non-aboriginal prospectors were prohibited from entering the area. However, as an offshoot of an 1874 military expedition under Colonel George Custer, gold was discovered in interesting quantities.[7] Despite the prohibition on entering Sioux land -- which was not seriously enforced -- a gold rush began that reached a climax about 1876. It is reported that "Many of the miners came up the Missouri River from Kansas," [8]next door to Missouri, and that many Norwegians -- apparently, including the Jeldness brothers -- were part of the stream.[9] The Sioux were outraged. Many moved off their reservations, organized alliances and assembled in a large, hostile group. The climax was the Battle of Little Big Horn in late June, 1876, in which George Custer's 7th Cavalry was annihilated, including Custer himself. Violence continued and the Hills were rather inhospitable territory for prospectors and miners until a couple of years later when the Sioux were attacked in strength by the US army, defeated and dissipated.

In this tumultuous period, several prospectors and miners, including some Norwegians,[10]were killed by the Indians, both before and after the battle of Little Big Horn.[11] I don't know if it was the widespread violence that repelled them or if they were attracted by the lure of better prospects elsewhere, but the Jeldness brothers soon left the Black Hills. Colorado beckoned.

Following the discovery of gold at Pikes Peak in 1859, there had been several "rushes" to Colorado, initially for gold and later for silver.[12] In the mid-to-late1870s the attraction was silver, high in the Colorado mountains. The excitement was intense, drawing people from all over the United States and abroad. The Jeldness brothers joined the silver rush to Leadville, Colorado, in 1877.[13]

Mining in Colorado

Generally, men joined a gold or silver rush intent on prospecting -- scouring unclaimed territory for signs of gold or silver, in streams or on land, seeking deposits that would result in a mine that would make them rich. That was probably the ambition of the Jeldness brothers, but I have no evidence of them prospecting in Colorado and, if they prospected, they did not locate a claim that developed into a mine. I have no information about their activities at their first stop in the famous mining camp of Leadville, but their stay there was brief. By 1878 they were in Poughkeepsie Gulch, San Juan County.

The first specific report that I have of the Jeldness brothers in Colorado is as ordinary miners, working underground. Thus, in a commentary on early days of mining in the San Juan region, Olaus noted that in "the later 70s" he was working as a miner, the partner of a man who later became a famous mining tycoon (see Annex 4, p. 102), drilling holes in the sides of the Alaska mine in Poughkeepsie Gulch, preparatory to blasting.[14] Drilling at that time and in that place was by hand, with hammer and “steel” (drill), either one man working alone ("single jack") or a two man team ("double jack"). In this instance, Olaus was part of a double jack team. One man held, turned and as necessary replaced the steel while the other wielded a sledge hammer. It was hard, dirty work, long day after long day, often in cramped quarters.

San Juan County is in the San Juan Mountain range, in southwest Colorado. It is part of the territory that was reserved to the Ute Indians and they jealously guarded their land, sometimes with violence. However, by 1870 some prospectors had edged into the mountains, finding rich deposits of silver. Pressure mounted on the government to do something about the Utes -- ideally, in the view of the miners, to expel them and open the area to prospecting, mining and non-Indian settlement. As a compromise, prolonged negotiations led, in 1874, to the opening of the area to prospecting and mining, but not to agriculture or settlement.[b] The silver rush to the San Juans then began. However, Poughkeepsie Gulchis remote, high in the mountains, about 10 tortuous miles north of the town of Silverton, west of the Continental Divide. For this reason, prospecting was late in Poughkeepsie Gulch and mining did not begin there until 1877[15]or 1878.[16] The Alaska mine must have been one of the early ones opened. The gulch is now uninhabited, with abandoned mine workings and a "few remaining ruins,"[17]a destination for adventurous four-wheelers (and the occasional geologist), over a rough, dangerous trail.[c] A recent atlas described the gulch as "very remote...(with)... horrid winters.”[18] Snow could arrive in October and not leave until May or June and the temperature could dip to 20, 30 and occasionally 40 degrees below zero. It is not a salubrious environment for mining or settlement.

It seems likely that the Jeldness brothers were among the earliest employees at the Alaska, but I don’t know when they signed on. They were relative neophytes at the silver-mining trade, with much to learn and the Alaska mine was in part their mining school. Thus, Olaus tells us that it was “in the mines of San Juan county” that the Jeldness brothers “accumulated respectable miners’ competence before ... (they) ... drifted to other fields.”[19]

Poughkeepsie Gulch must have been a rough and ready mining camp when the Jeldness brothers were there. The census taken in June, 1880,[20]recorded only 51 inhabitants in the vicinity of the Alaska mine, including Olaus[d] Of the 51 inhabitants, 49 were adult males, 47 of them miners (there was also a blacksmith and a baker). There was only one female, the wife of a miner, and with her was her 5-year old son. An additional 25 people were recorded living farther along the valley in the so-called “Gulch Town,” all of them adult males. As well as 20 miners, the town included a mine supervisor, a clerk, a blacksmith and two “speculators.” Poughkeepsie Gulch was hardly a normal, balanced community providing a comfortable style of living![e] The nearest point of semi-civilization was Silverton, 10 miles distant, with a population of a little over 500, but growing rapidly.

The Alaska mine was regarded as promising, with rich deposits of silver-bismuth ore, and "in 1879 and '80 this property was worked extensively, and a quantity of ore shipped, which netted a large profit."[21] However, in the difficult location of Poughkeepsie Gulch with its serious transport problems, a mine had to be very rich to survive, let alone prosper. Although a wagon road was built into the valley, the Alaska mine was on a mountainside above the gulch, at an altitude of 3,697 metres,[22]only accessible by a rough mountain trail that was "steep and dangerous," navigable by a "sure-footed burro" and little else.[23] Olaus reported that the Alaska mine ore "had to be sorted closely to bear transportation on burro" 150[24]or 100[25]miles to the nearest railhead, a staggeringly inefficient and expensive form of transport. This must have been near the beginning, because as the San Juan boom progressed wagon roads were gradually built into the region and concentrators and smelters were erected at various locations in or close to the county. In 1878 it was reported that ore from the Alaska was being delivered, to a new smelter at Lake City. Nonetheless, this was a haul, by burro and wagon, of about 25-30 miles. The railroad did not reach Silverton, about 10 miles from Poughkeepsie Gulch, until July, 1882,[26]after the Jeldness brothers had departed, and it was never extended to the Gulch. The wagon road from Silverton to the Gulch was passable only in the summer months and the winter could wreak havoc on it. Thus, for example, in late April, 1881, it was reported that although the snow was rapidly disappearing on the road to Gladstone, “several of the bridges will need to be rebuilt before the road will be passable for wagons.”[27] Gladstone was on the way to Poughkeepsie Gulch. The Alaska mine had a further complication. Unlike most mines, the rich silver-bismuth ore was found in discrete pockets, not in well-defined veins.[28] This made it more difficult to mine profitably. As a miner working in the narrow, dark, dangerous and poorly ventilated tunnels of the Alaska mine, Olaus would have earned about $3-$4 a day.[f] Even without the high cost of living in an isolated mining camp, these wages would not have made him rich -- but he was learning the mining trade.

Sometime late in 1880 the Alaska mine was shut down and not reopened until a new party leased it in late 1883, after the Jeldness brothers had left the state (an August, 1883 visitor said the Alaska looked "lonely and neglected"[29]). After the mine closed, the Jeldness brothers went into the mining business on their own account, becoming contractors in a mine called the Seven Thirty, probably in October, 1880.[30] Contractors did not own or lease the mine, but had a contract to do a specified amount and type of work, in a specified time period, for a specified sum of money. The contract could be profitable if the work could be done properly, on time and at low cost. Like many contractors, the Jeldness brothers probably did the work themselves, working long, hard hours.[g] However, the Seven Thirty does not seem to have been a great success as a mine. It was reported in June, 1881, that "a good strike" had been made,[31]but then references to the mine disappear from the press, a sign that all was not well. In an 1883 review of the mines of Poughkeepsie Gulch[32]and a later one of mines of the San Juan district,[33]no mention was made of the Seven-Thirty.[h] It seems likely that, like so many other remote mines, the Seven-Thirty did not survive for long.

Skiing in Colorado

San Juan County was blessed with heavy snowfalls. Snow drifts in the valleys could be 25 feet or deeper. Winter usually arrived in November and the trails normally were not open again until April -- and in some remote areas it could be later. It was reported that the snow was just beginning to melt at Mineral Point, at the end of Poughkeepsie Valley, in June, 1881. Not surprisingly, skis were a common means by which people got around in the winter and they were used for recreation. The skis, generally homemade, were wide and long and referred to as “snowshoes.” Thus, for example, a merchant advertised in La Plata Miner, a newspaper published in Silverton:[34]

ASH SNOW SHOE TIMBER

Dressed, two lengths, 10 and 13 ft. Only a few pair left ….

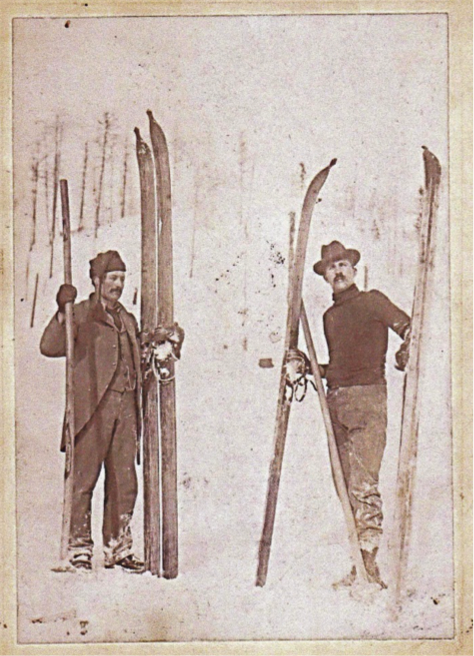

In his book, Mountains of Silver, David Smith reproduces two pictures showing a group of miners with their long, wide skis, close to the area where the Jeldness brothers worked.[35] One shows two prospectors resting in a snow bank and the other a group of miners engaged in a skiing competition (I wonder if the Jeldness brothers were among them). While skis were "snow shoes," what we now call snow shoes were also used, but were referred to as “netting”[36](in a letter written when he was in Rossland, Olaus called them “Indian webshoes”[37])

The Jeldness boys were in their element -- mountains and skis -- and they were noticed. Ole Jeldness was referred to in La Plata Miner as “the famous snow shoe runner ... (who) ... is still anxious to run for the championship of America.”[38] When, in late December, 1879, a popular member of the Poughkeepsie community got caught in a blinding snow storm, took sick and died in an isolated miner’s cabin, he was buried at Silverton. The funeral procession to the cemetery consisted of “40 men on snow shoes.”[39] Representing the Alaska Mine was Ole Jeldness. In the winter of 1878-79 the Poughkeepsie miners built a ski jump and held a jumping contest for a Sunday’s entertainment. Olaus and Anders, who were spectators, could not resist the temptation and, although they had only one pair of skis between them, on the spur of the moment took off and went over the jump -- each on one ski (see below, Annex 3, p. 99).[40] Ever competitive and, like good miners, playing for high stakes, on Christmas day,1880,the three Jeldness brothers issued a public challenge:[41]

SNOW SHOE CHALLENGE.

We, the undersigned, will at any time between now and the first of April next, run on snow shoes against any three men in America for $2,000 a side; or I, Anders Jeldnes, will run against any one man on the American continent for $1,000 and the championship of America. The race to be run in Poughkeepsie Gulch, San Juan county, Colorado, and according to the Norwegian snow shoe rules.

Ole Jeldnes,

Olaus Jeldnes,

Anders Jeldnes.

$1000 was more than a normal annual income for a miner. The challenge was published in the Silverton newspaper as well as in a Scandinavian newspaper published in Chicago. One response was received. A Laplander, visiting the camp, offered to race Anders, "conditionally."[42] He wanted to increase the individual prize to $2,000 and to change the route, racing from the peak of one of the mountains near Silverton to a well-known mine. Anders considered the proposal a ridiculous "bluff," refused it and reiterated the original proposal.[43] Apparently, the Jeldness brothers' reputations were such that no one took them up on the challenge on their terms.[44]

Norway

Why the Jeldness brothers left San Juan County is not documented. It seems likely that the two mines, the Alaska and the Seven Thirty, had closed around them, but there is some evidence that they did well enough as contractors on the Seven Thirty to be set up financially, so they decided to move on.[i] Perhaps they also had other profitable mining ventures that I do not know about. In any case, in the fall of 1881 the Jeldness brothers left Colorado and traveled to their ancestral home at Stangvik, Norway, "to pay our old father .... a visit."[45] Their arrival in Stangvik was marked by considerable fanfare. Having missed the weekly steamer from the regional seaport, Kristiansund, that would have taken them up the fiord, they hired a boat, complete with a canon, for the rest of the trip home. The canon was fired repeatedly as the boat approached Stangvik, attracting a crowd of townsfolk to greet them. The prodigal sons -- the long departed American miners -- had made a flamboyant return.

Olaus reports that while in the Norwegian seaport he was shown samples of ore from a new mine. The samples included some very rich specimens that, for unexplained reasons, had not been assayed. Intrigued, and accompanied by one of his brothers, he went to see the mine. What they found was a badly managed mine, with very rich ore, some of which had been incorrectly identified. Recognizing the mine's potential, the Jeldness brothers began to buy shares of stock in the company. The directors, who were local bankers and business people, not "mining men," were curious about their activity in the market and asked to meet. Taken on a tour of the mine, Olaus so impressed them with his knowledge of mining and his ability to visually assess the value of mineral specimens that they offered him the management of the mine -- at age 25. In his Reminiscences, Olaus reported that he picked the prime locations to mine, trained the miners in Colorado mining techniques and developed an efficient operation. The result was a profitable mining venture that set off a mining boom in the area. Olaus did not state the location of the mine in his Reminiscences, but another story placed it somewhere in the northern part of Norway.[46]

Mining School?

After two years working the Norwegian silver mine, Olaus "again heard the irresistible call of the wilds of the rocky Mountains of North America."[47] However, he did not return to the Colorado silver mines. According to one report, he enrolled in a mining school.[j] I am skeptical. Given Olaus’ extensive mining experience and restless temperament, it would be surprising if he found the nature and length of a university course of study to his liking. If he did so enroll, he attended only briefly and never mentioned it in any of his surviving reminiscences or public utterances. If he arrived in Norway in the fall of 1881 and spent two years managing a silver mine, the earliest he could have left Norway was late in 1883. He began his prospecting trip to northern Idaho sometime in 1884, leaving a potential gap of little more than a year, if that. He might have begun a program, but a mining engineering course was then three or four years, depending on the university.[48] In any case, he did not have a mining engineering degree, even though in many newspaper stories, particularly later in his life, he was referred to as a mining engineer. Occasionally, such as on the 1927 birth registration for a daughter born in Rossland,[k]he identified himself as a "mining engineer," but normally he referred to himself simply as a "miner" or a "mining expert."[49] Many people recognized as mining engineers in the American west at this time, including some of the best, lacked the requisite formal education and degree.[50] They had learned their trade on the job. Olaus was among that group -- a mining engineer "trained in the school of experience."[51] At times he was also referred to as a "geologist"and so employed.[52]As an extension of his on-the-job training, in a talk on geology to the Northwest Mining Association he said that he learned geology "from men, books and observation."[53]

Having left Norway at age 16 he would have had little more than a basic education. Although perhaps not highly educated, it seems clear that he was a man of great intelligence with a practical bent, capable of self-study and learning on the job. Perhaps we should regard him simply as one of the species, "practical mining man" -- a man of very considerable intelligence, practical ability and wide experience, who was "looked upon with far more confidence than the geologists and engineers issuing from the few limited mining schools of the country."[54]

Idaho and the Arlington Mine in Washington State

If he had attended a mining school, Olaus soon quit and continued his peripatetic ways. Drawn by a new gold-silver rush, he went to the Murray-Pritchard camp in the Bitterroot Mountains of Idaho's northern panhandle in 1884.[55] I have no information about his activities there, but he must have been sufficiently successful to build a stake for his next venture. In 1886 or 1887 a new boom in Okanagan County, Washington State, attracted him. In the words of the Toronto Globe, he was “the man who made the Arlington mine.”[56]He bought and did development work on the claim that became the Arlington, a silver mine on Ruby Hill, about 16 kilometres northwest of Omak, Washington, on what had been the Moses Lake Indian Reservation.[57] The reservation was legally abolished on July 4, 1884, but was not opened to non-Indian settlement and mining until May 1, 1886.[58] Soon after, a group of prospectors staked several rewarding claims on Ruby Hill, including the Arlington.[59] The mine tunnel still exists and can be seen by a short walk from the hamlet of Concully, Washington.

I don't know when Olaus arrived or when he purchased the claim, but in June, 1887, it was reported that a syndicate from Oregon acquired the mine for between $27,000 and $45,000 (between $630,000 and $1,050,000 in today’s dollars), [l]a small fortune in 1887. Olaus is not mentioned in stories about the transaction, but he must have sold his interest in the claim to the syndicate. To develop and operate the mine, the Portland syndicate incorporated the Arlington Mining Company, headed by Jonathan Bourne, who was later elected a United States Senator from Oregon and who was to play major role in the next phase of Olaus' life. I don't know how much Olaus paid for the claim or what he had spent on development work, so I don't know how much he profited from the transaction. He must have had at least one partner in the claim because he later said that he had a 50% interest, so whatever the net sum, half was his.[m] I also don't know if Olaus received any cash for selling the mine. He later owned shares of stock in the Arlington company, so he was probably paid at least in part and perhaps almost entirely in shares, as was common in such transactions. If so, his new wealth would soon become nebulous.

One of the new owners, George Sheppard (or Shepard), was appointed superintendent of the Arlington,[60]so Olaus may have had little or no involvement in the operation of the mine after its acquisition by the Bourne group. However, he must have made a good impression on Bourne as a miner and as a person. Olaus and Bourne became business associates and Bourne placed considerable trust in Olaus in various business dealings. Olaus regarded Bourne as a friend; how strongly the feeling was reciprocated is difficult to tell. They carried on a lengthy correspondence about mining matters, some of which survives.[n] Olaus was in Spokane in July, 1887, but it is not clear whether he was working for Bourne (he identified himself as a miner).[61] The first certain example that I have found of Olaus acting as an agent for Bourne was in March, 1888, when he went to Chicago in an attempt to sell shares in mines in which Bourne had an interest.[62] How successful he was, I don't know. He must then have spent some time essentially unemployed in Portland. In late February, 1889, he wrote to Bourne from Spokane that "My occupation here is the same as when in Portland -- that is to say nothing."[63] Soon thereafter Olaus accepted a proposal from Bourne. The nature of the proposal is not explained in Olaus' letters, but in late May he was still in Spokane, trying to purchase a mining property for Bourne, and encountering serious resistance because of the price he was authorized to offer.[64] In October, 1889, although then engaged in mining in Montana, and again in October, 1890, he was said to be a resident of Portland when he attended meetings of the Oregon State Secular Union (see below, p. Error! Bookmark not defined.). He must have spent a good deal of time on train trips between Portland, Spokane and central Montana.

Montana

In July, 1889, Olaus was in Montana, on a much larger assignment. Bourne and Olaus had "bonded" six related silver mines called the Iron King group at Spring Gulch, in the Bitterroot Mountains about half way between Missoula and Kellogg. The contract, called a "bond" or a "working bond," was the common method of providing for the assessment of an underdeveloped mining property in the Pacific Northwest, on both sides of the border, by parties interested in purchasing the property. A bond was a cross between a lease and an option.[65] Its terms could vary widely and, of course, were subject to negotiation, but the basic concept was that the working party, in this case Olaus and Bourne, would take possession of the property, develop and work it for a specified maximum period of time and then make a decision whether to abandon it or purchase it for a predetermined price. It was a method of dividing the risk of an uncertain venture between the owner of the property, perhaps the prospector who discovered it, and a potential purchaser, while giving the potential purchaser the opportunity to assess the value of the property by actually working it before making a final commitment. In the case of the Iron King group, Olaus and Bourne were already part owners (each held a 1/32 share),[o] so the bond was between Olaus and Bourne on the one hand and the several other shareholders on the other.

For the Iron King venture, Bourne, who was a financier and not a “mining man,” remained in Portland. He provided the funding and had the upper hand in critical decisions, while Olaus provided the mining and mine management skills, on site. He hired workers, arranged for the necessary equipment and supplies, decided on which of the mines to work and on a plan of development, supervised the mining activities, worked in the mines himself and made weekly written reports to Bourne. Olaus, enthusiastic about the mines, thought they were going to make fortunes for both men. Thus, when asked in October, 1889, what it would take for him to give up his interest in the properties he said $25,000 before December 13 and $50,000 thereafter, based on his assessment of the prospective value of the mine.[66]For the times, these were enormous sums (over $600,000 and $1,200,000 in today’s dollars) that Bourne called "ridiculous."[67] Bourne hired two other experts to inspect the mines; both gave much less enthusiastic assessments. After their visits, Olaus acknowledged that "unless richer ore is discovered pretty soon the undertaking (I hate to say it) becomes a failure," but he was still optimistic that rich ore would be found and urged renegotiation and extension of the bond.[68]

Despite the lukewarm assessments by the two mining experts and perhaps a measure of his respect for Olaus’ abilities, Bourne agreed to attempt to extend the bond and entrusted Olaus with the negotiations, for which Olaus returned to Spokane where he met with some of the other principals. Their discussions continued from early February to mid-March, 1890, but ultimately foundered on the unwillingness of one of the owners to accept Bourne's terms.[69] Olaus then made a quick trip to the mine, walking several miles from the railroad station, through deep spring snow, in mountainous territory replete with the threat of avalanches, to get there, and close the mine.[70] He returned to Spokane, in debt to Bourne for his personal expenditures and, as he said, "dead broke."[71] He apologized for the failure of the venture but continued to assert that the project could have been a success if the bond had been extended.

Although Olaus had earlier expressed such confidence in the future of the Arlington mine that "I will not dispose of a single (Arlington) share unless necessity compels me to do so,”[72]as his personal financial situation worsened over the winter, he sought to sell some of his Arlington holdings, but could find no buyers.[73] Financial relief came in the form of another assignment from Bourne. Olaus was dispatched to assess potential mining properties in the vicinity of Lewiston, Idaho, about a hundred kilometres south of Coeur d'Alene.[74] He spent about two months on horseback visiting properties, but found nothing of interest.[75] Upon his return to Spokane, on his own suggestion, he was dispatched to the Olympic Peninsula in Washington State to investigate recent discoveries of copper, but dismissed them as small in quantity and low in value.[76] While Olaus was ruminating about possible prospects in the Similkameen district of British Columbia and Granite Creek in Idaho,[77]Bourne peremptorily ordered him to go to the First Thought mine, near the Arlington, to fill in for the superintendent who was ill. Olaus went "reluctantly" (he wanted to go to Montana), but he went.[78] He later acted for Bourne in an attempt to sell the First Thought to representatives of an English concern, but failed.[79] In the fall of 1890 he explored other properties near Coeur d'Alene and Wallace, Idaho, either for himself or for Bourne, again to no avail.

Over the winter, 1890-91, Olaus was in Spokane and probably spent some time at the Ruby Hill mining camp. In mid-February, 1891, the Ruby Hill Mining Company, a new company, based in Spokane, was incorporated.[80] Olaus Jeldness was Secretary and his brother Andrew Superintendent of Mines. The company owned three claims on Ruby Hill, the Adelphi, Mohawk and Mountain Queen, each bordering on, or close to, an established, producing mine. The Adelphi adjoined the Arlington Mine ("a property of great value") and the Mountain Queen was a stone's throw from the First Thought ("valued at a million dollars or more"); Olaus had been instrumental in creating the Arlington and had a passing involvement with the First Thought. Andrew's role in the Ruby Hill company is interesting. This is one of only two instances in which I have found a direct relationship between the brothers in a mining venture. I don't know how successful the Ruby Hill company was. I have found no more information about it, so, like many such companies, it probably just faded away as its mines proved unrewarding.

In April, 1891, Olaus was again in Spokane, acting for Bourne, attempting to sell shares in the First Thought mine, on commission. He was to receive anything over $2.00 that he could obtain for the shares, but was not to accept anything less than $2.50.[81] Spokane was in the grips of financial stringency with interest rates in the range of 2% a month and up.[82] Not surprisingly, Olaus could not find buyers for the shares. Olaus' efforts as Bourne's financial agent in Spokane were not a roaring success!

Apparently the owners of the Iron King group, after refusing to extend the bond of Bourne and Olaus, decided to open the mine and work it themselves. They hired Olaus, the man who knew the mines better than anyone. The nature of his position is not clear. It is possible that he was the superintendent, but he reported to his friend, Bourne, that:

They are doing considerable development work at the Keystone and I do their surveying. As I am hired and is under the same rules as any other man I obey orders without comment. I work as miner, house builder or surveyor at $3.50 per day and I do the “outfile” business correspondence and bookkeeping at night for which they have agreed to pay me $1.50 per day.[83]

He was a man of many talents who worked very hard -- perhaps too hard, because “I come home at nights from work (I live in town on acct. of the bookkeeping business) my brain is dull and my hand shivers and they refuse to respond.”[84] He would not get rich working as he did, or even pay off his debts, but he could put bread on the table with a little left over.

Over the winter, the owners of the mines incorporated themselves as the Keystone and King Mining Company (reorganized in 1892 as the King Mining and Milling Company)[85]. Olaus appears to have done much of the paperwork and somehow paid for his share of the costs to effect the incorporation. His part interest in the mines meant that he ended up with shares in the new company; shares that he planned to sell to obtain "enough money to put me on my feet again."[86] He then saw an opportunity to get out of debt and become rich. He used what money he had saved from his work over the winter to obtain a bond, this time for himself, on another nearby mine, the Little Anaconda. He noted that "I have no partners and I have not got one dollar ... but I have some credit."[87] When the "credit" that he thought was available proved illusory, he reluctantly sold some of his shares in the Keystone and King company to provide supplies for the mine.[88] Working hand to mouth, he hired some miners, paying monthly expenses of $1,000 by shipments of ore to a smelter.[89] He ordered crushing equipment so that he could ship crushed ore, ready for the concentrator, reducing transport costs and increasing his net return, but he could not raise the $2,500 required to pay for it.[90] The crusher sat in storage in Helena while Olaus seethed because the Keystone and King company, which he had worked so hard to create, named a shaft in the mine after him ("the Jeldness Shaft," which offers a delightful double entendre), but would not extend credit so that he could pay for the crusher.[p]

It was a very difficult time for the operators of silver mines. In 1873, in what the silver interests called the "crime of '73," the United States had stopped coining the standard silver dollar and had abolished the official $1.29 per ounce price at which the United States Treasury would buy all of the silver offered to it. For years, the world market price of silver had been higher than $1.29, so little if any was sold to the Treasury and silver dollars essentially disappeared from circulation. Soon after the "crime of '73," however, production of silver increased significantly (in part a result of discoveries in the western states) and the market price fell below $1.29 per ounce. There were pronounced fluctuations, but the trend was strongly downward (see Figure 1, p. 22)[q]. By 1891, on average, the market price of bar silver in New York was in the neighbourhood of 98 cents an ounce The politics of silver were intense as western silver interests -- the "free silver" movement that included Jonathan Bourne among its members -- attempted to persuade Congress to again buy unlimited amounts of silver at $1.29 per ounce.[91] As the congressional support for the silver lobby waxed and waned, adding a speculative factor to the ebb and flow of market forces, the price of silver oscillated, but the general downward trend continued. By 1893 the average New York price had fallen to about 77 cents and by 1894 it was about 63 cents an ounce. It was not a great time to be opening a marginal silver mine.

Figure 1

Price of Bar Silver, New York and London, Mid-month, 1890-1894

Although the Toronto Globe reported that in his Montana ventures Olaus "was on the high road to becoming a multimillionaire"[92] -- undoubtedly his own optimistic assessment of his situation -- he was in fact engaged in a losing battle.[r] He struggled on through the winter of 1892-93, almost isolated in his cabin

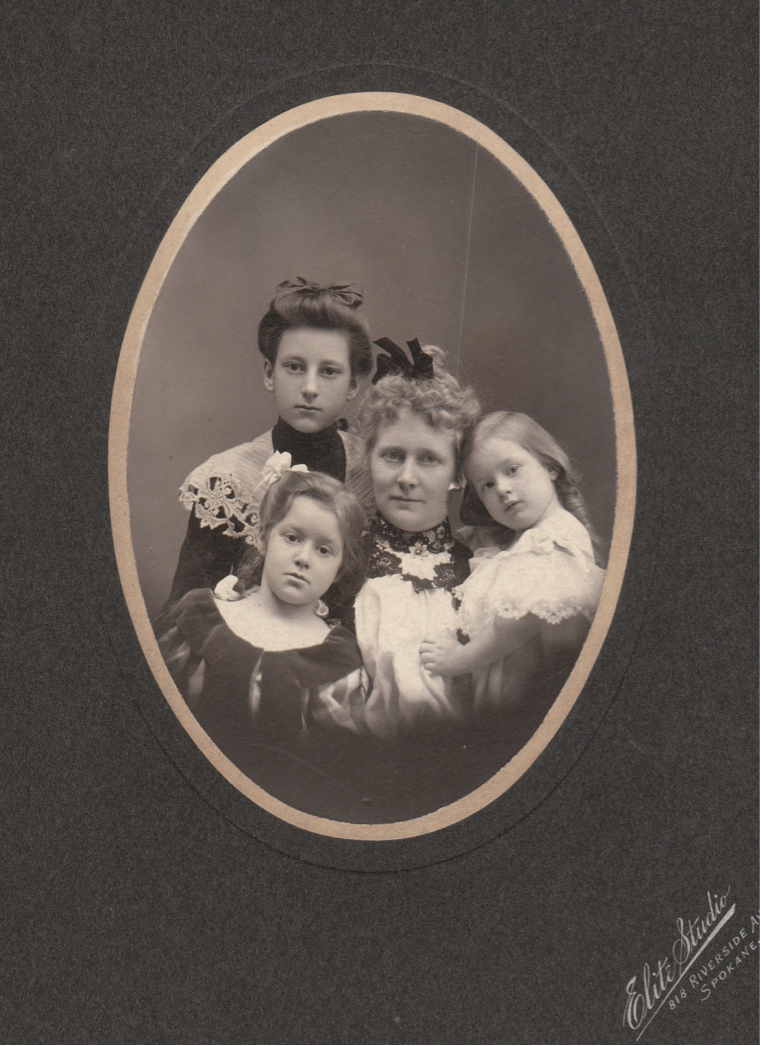

… the mine that I am working is situate (sic) 5 miles from Carter and 2000 feet higher and as I have my wife & child at the mine I leave it only about once every week when I run down on snowshoes (i.e., skis) after mail and return in a few hours.[93]

Olaus had come to Montana in November, 1891. Sigrid must have stayed in Spokane with their first child, Randie, who had been born there in May.[94] With the young baby, she had joined Olaus at the mine in November, 1892, just in time for the winter to set in. He worked hard for long hours, but as is so often the case the real hardship was borne by his wife. Poor and isolated in a small, snow bound cabin, with a very young baby and the nearest medical care a five mile trek through the snow, and with a husband who was increasingly distraught about their uncertain future, she must have become seriously distressed. When the summer came Olaus told Bourne,

Discouraged and sore at heart I moved my wife and child from the mine to Carter on July 1st. She had not then seen a person of her sex for seven months and 11 days.[95]

I don't know where she was over the following winter.

As the price of silver continued to drop Olaus found that his sales of ore would not cover his costs.[96] To keep going he managed to borrow from a local bank, pledging his remaining shares in the Keystone and King company as collateral. Then, the sudden drop in the price of silver in July, 1893 (see Figure 1, p. 22) provided the "knockout blow."[97] He deeply prized the shares.

This stock alone would make me a fortune in ordinary times .... If I lose my stock at present in the Bank the last ray of hope of ever being able to rise above an ordinary laborer vanishes."[98]

In late August, 1893, he made a desperate appeal to Bourne to lend him money or to purchase his shares from the bank.[99] When his appeal failed, he closed the mine and cast around for some method of supporting himself and his family.

Relief again came through the King group of mines. A local storekeeper obtained a bond on the Keystone, now the leading mine in the group, and hired Olaus, again at $3.50 a day, to manage the operation.[100] He was uncharacteristically discouraged and depressed, facing another winter of isolation.

... if hard luck persists in following me much longer it will weaken instead of strengthening my ambition and hope and I shall become reconciled to the lot of the majority of men here -- namely a log cabin and a rifle.”[101]

Unfortunately, his activities that winter and the following summer are not documented in his correspondence. He presumably continued to work in the Keystone mine, but eventually he left Montana, a disappointed man. The hoped for riches had not materialized.

ROSSLAND

After an interlude working as an ordinary miner in Montana, in November, 1894, Olaus went to Spokane, looking for his brother, Anders, but he was not there.[102] It is no doubt while he was in Spokane that Olaus heard about the Rossland gold rush and off he went to seek his fortune, chasing another mining bonanza. He arrived in Rossland sometime between November 15, and November 29, 1894.[s] Apparently, he had received a windfall of $200 from his Montana venture (see below, p. 62). It was a substantial sum at the time and must have been much appreciated by Olaus, given his financial state. He took a job at the Josie mine. The Josie became one of Rossland's premier mines, but at that time it was a partially developed property that was closed for the winter. The owners were in the east looking for money to further develop the mine, leaving Olaus as the only employee. Effectively, he was a caretaker, but he expected to become the superintendent when the mine reopened in the spring -- and in the meantime he could not resist being a prospector. He reported that he found a large body of ore on the Josie property of which the owners were not aware and was going to ask to have the find bonded to him so that he could seek capital from Montana friends to develop it to his own profit.[103] Olaus left the employ of Josie on January 1, 1895. He said that he departed so that he could operate “independent of anyone,”[104]but given his interest in bonding a section of the Josie site, it is not obvious that the severance was voluntary. The owners may not have looked kindly on his attempt to obtain part of their valuable property, even though he had discovered it. They would have discovered the mineral deposit later, in any case.

Olaus then became an independent prospector, in some cases working with others. He reported that several claims in which he had a partial interest were promising and had been bonded to various large concerns with substantial option prices attached and reported confidently that “I expect to succeed here.”[105] Probably because of the experience in the remote cabin in Montana, he had not brought his wife and child to Rossland with him. They had been in the east for 10 months (Sigrid had family in Michigan), but in early August, 1895, having built a “nice house” opposite the court house on Columbia Avenue, Rossland's main commercial street, he brought them to Rossland.[106] However, the mining firms that had bonded his claims chose not to act on their options to purchase. He did not receive the large sum of money that he had expected and in October he reported that he had been “broke all summer.”[107] Being broke must have been something of an exaggeration -- or perhaps a relative term -- if he acquired land, built a "nice house" and, as noted below, acquired claims on Sophie Mountain. In any case, a mining claim on remote Sophie Mountain would soon provide him with a handsome return.

The Velvet Mine

The Velvet mine was situated several kilometres southwest of Rossland, across a formidable array of mountains that provided a dramatic backdrop to the city. The mine was on the far side of Sophie Mountain, very near the US border and overlooking the valley of Big Sheep Creek, one of the major creeks in the district. The discovery of the Velvet claim was a direct result of the earlier discovery of two other gold-copper claims, the Victory and the Triumph, on Sophie Mountain "by American prospectors who came up Big Sheep from the Colville Indian reservation in the summer of 1890."[108][t] I don't know if Jefferson Lewis, an American, born in Missouri, was among those prospectors. When he was married in Rossland in 1897 he described himself simply as a "miner,"[109]not as a prospector, but other than that I know nothing about his background. In any case, whether by discovery or by purchase, Lewis acquired shares in both the Victory and Triumph claims and in late June, 1896, sold a quarter interest in them to Olaus.[110] There must have been at least one other partner in the ventures because Olaus subsequently acquired the interest of H.F Jacobson in the Victory.[111] I have not discovered if he similarly increased his interest in the Triumph, but the two claims were soon merged, to be known as the Victory-Triumph claim.

Lewis and Olaus developed the Victory-Triumph claim to the point at which it would be attractive to larger mining companies. In the process they recognized the potential of the area around the claim and quickly expanded their control of the richest part of the mineralized belt of the western side of Sophie Mountain, acquiring the nearby Portland and Bluebell claims (apparently for $5!)[112]and discovering the Velvet in the process. Olaus staked the Velvet claim on behalf of himself and Lewis in September, 1896.[113] Thus, by purchase and discovery, by late 1896 the partners owned four promising claims and had done sufficient development work to show that the Victory-Triumph, Portland, Bluebell and Velvet had potential as copper-gold mines. In May, 1897, Olaus and Lewis sold the Victory and Triumph claims to a British mining company, Kootenay Goldfields Syndicate, reportedly receiving $20,000 each.[114]

New people then arrived on the scene, the representatives of a recently organized British company, New Goldfields of British Columbia. They inspected the Velvet and in August, 1897, purchased it for a reported $62,500,[u]$12,500 in cash and the balance in shares of New Goldfields.[115] In dollars of today's purchasing power, $62,500 would be about $1.8 million and $12,500 about $355,000. Another claim, the Portland, that was close to the Velvet, was said to have been discovered by John Cromie, a business associate of Olaus in Montana, in April, 1896.[116] It must have been acquired by Olaus and Lewis along with the contiguous Bluebell claim soon thereafter. Both claims were almost adjacent to the Velvet and New Goldfields purchased both from Olaus and Lewis in the fall of 1897, the Portland for $19,000[117]and the Bluebell for an undisclosed sum. The company also purchased some contiguous areas that were smaller than regular claims ("fractions")[v]from Olaus and Lewis.[118]

The companies that New Goldfields spun off to operate the mines were not successful, in large part because of problems in transporting the relatively low grade ore to a smelter and with water (too much underground, not enough above ground).[w] The companies went through a succession of reorganizations, each following the exhaustion of their funds, and within a few years had been liquidated. The Velvet continued to produce sporadically into the 1980s, with successive operators taking out considerable amounts of ore, but eventually giving up because of myriad problems. The Velvet and the associated properties were never major mines.

Despite the ill fortunes that later befell the operators of the mines on Sophie Mountain, Olaus and Lewis had become, by the standards of the day, moderately wealthy men.

The Number 1 Claim

Little is known about Olaus Jeldness' other prospecting and mine development activities in Rossland. However, we do know that he was involved with the mining claim called the Number 1, located on Red Mountain.

In 1906, Thomas Greenough, a retired railway contractor and sometime prospector living in Missoula, Montana, reminisced about his life on the western frontier, noting that

Nearly eight years ago Larson and Thomas Wren and Olaus Jeldness and myself sold the No 1 at Rossland for $175,000 to the British America corporation. That was a mighty good sale, for there was only a 10-foot hole on the property.[119]

It was, indeed, "a mighty good sale." At first glance, the reported price seems high for what was simply a "prospect," not a mine of proven quality. Other prospects in Rossland were changing hands at prices in the thousands or tens of thousands of dollars. However, the Number 1 was one of a cluster of mines and claims in the most prized mining area in the mining camp. It was adjacent to the Josie and the War Eagle mines, both properties of already proven value, and but one property away from the Le Roi, the richest and most famous of all Rossland mines. This cluster of properties surrounding the Le Roi is shown on Map 1 (page 29). Perhaps location justified the high price.

The Number 1 was located in June 1890, long before Olaus arrived in Rossland, by someone called Samuel Creston.[120] By 1895 it was owned by another miner, William Springer. Thomas Greenough, Peter Larson and Thomas Wren, based in Montana, individually and in various combinations of partnerships were involved in railroad construction, mining, smelting, real estate and banking throughout the American northwest and plains states. They were wealthy capitalists, always on the hunt for potentially profitable investments, including mining properties. They did not seem to want to get into the long term business of operating mines. Rather, they sought promising prospects, developed their potential and sold them at a substantial profit.[x] Both Wren and Larson were in Rossland in 1895. Thus, in January of that year, it was reported that "Mr. T.F. Wren, of the firm Wren and Greenough, railroad contractors, is looking for investments here and is now figuring on several propositions."[121] Later, in June, "Peter Larsen (sic), the railroad contractor is in town."[122] The announced purpose of Larson's visit concerned the construction of a railway between Rossland and Trail,[y]but he could well have been looking at mining properties at the same time. In any case, in February, 1895, it was reported that "Thos. F. Wren has bought in half interest in the Number One on Red Mountain from William Springer."[123] Although in April it was reported that "Bill Springer is hard at work on the No. 1," that was the last we hear of Bill Springer. The Montana men must have bought him out. In the meantime, a richly-funded, English company appeared on the scene and began splashing money about, buying and optioning mining properties. That company had fixed its eyes on the Le Roi mine, the cluster of properties surrounding it and other properties on the same "ledge" or body of mineralized rock that extended across the north side of Rossland. Finally, in mid-December 1897, it was revealed that "... the No. 1 on Red Mountain has been sold to Alexander Dick for $200,000 with cash payment of $50,000"[124]. Mr. Dick was the agent for the London and Globe Finance Corporation, which was busy organizing a subsidiary, the British America Corporation to own and operate the many properties that it acquired in Rossland and elsewhere in British Columbia and the Yukon.[z] It was not stated if the balance was in shares or deferred payments. Mr. Dick refused to confirm or deny the rumour, but observed that the report contained "some inaccuracies."[125] This suggests that the cited price or terms may not have been quite correct, but the rumour certainly gives credence to the Greenough story that the group sold the Number 1 for $175,000.

Map 1

Map showing location of the Number 1 claim

What was Olaus' role in all of this? The direct answer is, I don't know. He may have used the proceeds of the sale of the Velvet and other properties on Sophie Mountain to participate financially. But he probably also had a more fundamental role. He had been employed at the adjacent Josie mine in December, 1894, (see above, p. 24) and because of his prospecting activities on that property (did he wander over the boundary to explore his neighbours' lands?) he would have become familiar with the geology of the area, including the geology of Josie's neighbours and he would have developed strong insights into the potential of the Number 1. That knowledge may have been key to the Montana men's speculative purchase of the Number 1. I have no evidence that the Wren-Greenough-Larson group were the "friends" in Montana that Olaus hoped would finance his acquisition of an option on part of the Josie property, but it seems likely. Indeed, it may have been an approach from Olaus that brought Wren to Rossland. In any case, Olaus would have been exceptionally useful to the Montana capitalists advising them of the qualities of the claim and, in the months between the purchase and resale of the Number 1, supervising, if not participating in, development work (the "ten-foot hole") designed to better illuminate its mineral potential. I don’t know how large a share of the proceeds Olaus received, but it provided some addition, small or large, to his tangible wealth.

Skiing

The quest for wealth was central to Olaus Jeldness' life, but it was not the only thing that was important to him. Skiing and ski jumping were also vital to his well-being. Thus, in a poetic letter to his friend Bourne, who was experiencing a financial setback, he referred to hardships experienced while he was prospecting in Idaho or Montana, while offering optimistic counsel and urging the mining speculator to spend some time in the great outdoors:

I know the difference between riches and poverty. I have tasted the sweets of plenty and although life to me seems under all conditions pleasant, with riches this earth to me becomes Paradise…. When adversity overtakes us despondency follows as a rule, then the best cure of all is to go out and get acquainted with rough nature. It makes us feel the insignificance of ourselves and our small troubles. Many a time have I stood with rifle in hand on the slope of some peak of the Bitterroots, admiring the sublime view and in exuberant spirit exclaimed ‘The world is mine.’ At the same time I probably did not know where the following day’s food for myself and my family were (sic) to come from unless I brought home a buck.[126]

Any outdoor activity could revive the spirits, but the ultimate cure was a ride on skis down a steep mountain side. Thus, in an 1893 letter to Bourne, he eloquently expressed his deep passion for the sport:

...snowshoeing is good (but) I look forward to the pleasure of skiing over cliff and crag and down steep mountain sides with childish glee . During the few moments I occupy in running the distance I am a boy again, my many disappointments and struggles in life is (sic) forgotten as I pass with more than Nancy Hawk swiftness over distances, sometimes down ugly gulches then bouncing over cliffs sailing 40, 50 & 60 feet in the air which however never checks the progress and while the run lasts the pleasure to me is sublime.[127]

He adopted the counsel that he had given to Bourne, enthusiastically skiing on the mountains around Rossland, particularly on Red Mountain.

All Rosslanders have heard the story of how Olaus, with his exploits in ski jumping and racing down Red Mountain, brought skiing to Rossland in the late 1890s.[128] He reveled in it himself, but he also wanted others to enjoy the experience. A ski club was organized as early as 1896 or 1897. Stories about a planned ski race down Red Mountain in March of 1898 refer to Olaus as president of such a club.[129] Another story in October 1898 describes the organizational meeting of the ski club for 1898-99.[130] Olaus was again the president.

In addition to being a great skier, Olaus was a natural publicist and promoter. His stunts on skis are legendary, as is his generosity to his friends. The hallmark legend involved a "tea party" for 25 friends on top of Red Mountain to celebrate the sale of "a mine," usually assumed to be the Velvet and so stated in one of the early reports of the event,[131]but not in the earliest one that I have found.[132] The date of the party is not noted in the sources. Olaus' major sale -- the one that made his fortune and hence the one most worth a grand celebration -- was the Velvet. However, that sale occurred in August, 1897, hardly a time for a ski party on Red Mountain. If the sale of the Velvet was the reason for the party, it was probably held in March, 1898, when there was still snow on the face of Red, but the risk of extreme cold and early darkness were less of a problem. The same timing is likely if the occasion was the sale of the Victory-Triumph, which occurred in May, 1897. The third possibility is the sale of the Number 1 to the British America Corporation in December, 1897. The party could have been held then, but a March 1898 party would have been a more attractive option -- perhaps to celebrate all three sales. However, one source reports, tongue in cheek, that "Olaus Jeldness left Rossland hurriedly after this ... and has had to live in Spokane ever since."[133] Taken literally, this would imply that the party was in March 1899.

Whatever the date, according to the legend, the guests struggled up the mountain in deep snow, fortified along the way with generous draughts of liquor, either from bottles discovered in snow banks or supplied by helpful attendants, to be met by a joyful Olaus, at an open fire, merrily cooking an elaborate feast of Norwegian delicacies, including thirst-inducing salt fish.[134] When the feast and the party were over and the thirsts were slaked, it is said that Olaus equipped each guest with skis for the descent of the mountain, which was steep, partially forested and dotted with mine workings. They were met at the bottom by an ambulance, a doctor and a journalist.

Not all of the participants in the tea party are known, but they included some of the leading citizens of Rossland, some of whom were reported to have been seriously injured.[135] Ross Thompson, the prospector turned real estate and security broker who had laid out the townsite and after whom the city was named, was said to have been "seriously wounded in both legs and arms and ...(had)... his head badly cut from the diorite and hornblende rocks." Lionel Webber, manager of the Silica Reduction Works and a member of the ski club, reportedly "lost three ribs and his left knee cap and had numerous wounds from unfriendly formations." Jim Sword "landed on Red Mountain railway tracks ... with a broken nose." "Frank Lascelles had one of his legs broken in three places and lost his voice." Joe Deschamps, co-owner of the major local sawmill, "boasted of losing only a pound or so of white meat." The fates of the other 20 participants were not individually recorded, but:

... every guest in that open air banquet of Jeldness' was done to a turn, with the exception of mine host, who made the world's record in ski jumping -- 319 feet and two inches -- covering the entire distance of nearly three miles in 1 minute and 53 seconds, landing at the Allen House bar on both feet and boasting of having had a most enjoyable time.[136]

No one man escaped bruises, concussions or broken bones in that "glorious" adventure, and some of the party carried the marks of the event for the rest of their lives.[137]

The 300-foot jump took Olaus to the Allen bar. Another curious assertion is that

One man, having descended the hill in one piece, piled good fortune on a fine evening by swearing that he had literally "lit" on a good showing of ore which he would make haste to record.[138]

To this, another source added,

I think it was Archie Mackenzie whose body jarred loose the first showing of pay ore on the Monte Christo mine.[139]

Whoops! The Monte Christo mine was on a different mountain.

Quite apart from the obvious hyperbole, as described the whole affair has an aura of improbability. Could anyone -- even the notorious risk-taker, Olaus Jeldness -- be so irresponsible as to send a group of his inebriated friends, at best neophyte skiers, down a mountain slope that he considered steep and dangerous for even expert skiers,[140]at dusk or in the dark (Whittaker suggests the party occurred in the evening[141])? The hillside was replete with brush, stumps, trees, large rocks, gullies, benches and mine workings. Serious injuries were almost certain.[aa]

Did the famous tea party happen? If so, are the details of the common tale reasonably accurate?

Some of Olaus' descendants vigorously assert that the party was held much as described in the literature. Similarly, Whittaker insists that it happened, but wondered "How much of the story is fact and how much fancy...?" What is perplexing is that I have not found a single contemporary newspaper account of it. As described, it was such a dramatic event, with injuries to so many prominent residents, that it should have attracted considerable attentionby local newspapers, hungry for local news. The Miner and the Record regularly reported on much more benign events. Would a newspaper that reported that

Ross Thompson has been suffering for the past two days with a severe cold, but is much better and will probably be around today,[142]

not have given extensive coverage to the city's most revered citizen if he had suffered very serious injuries on a skiing escapade? Similarly, would a newspaper that reported that a relatively unknown, recent resident

was run into by a sled at the corner of Columbia avenue and Spokane street. The sled struck him fairly above the right ankle and the bones snapped clean,[143]

not have commented on the shattered leg suffered by one prominent citizen and the broken ribs of the manager of one of the major enterprises in the area, the Silica Reduction Works, while skiing on Red Mountain? It is all very puzzling.

The oldest report on the tea party that I have discovered is a column by Cheney Cowles, published in the Spokesman Review in 1933, 35 years after the tea party's likely date.[bb] The article cites an undated letter from "a contemporary journalist, Hector McRae," to a Spokane resident, as the source of the information about the party and the injuries. McRae asserted that he "accompanied Dr. Bowes in his ambulance to bring in the dead and wounded,"[144]making his a contemporary account. However, the letter is not available; it may have been written long after the event, relying on memory and embellished for effect. A similar account by Sydney Norman appeared in the Vancouver Sun in 1935, either drawing on the same McRae memoir or on the Spokesman Review story. These articles aside, the primary account of the tea party is in the 1938 Historical Edition of the Rossland Miner.[145] The main subsequent expositions are in the 1949 history of Rossland by Lance Whittaker and the more recent book by Jordan and Choukalos, but there are many others.[cc] These secondary sources provide neither a date for the party nor a source for the story other than memories of "old timers."

A celebratory tea party probably occurred, but the details reported in the literature are surely gross embellishments.[dd] Apparently an elaborate celebration of the sale of a mine was a custom in Rossland; Jefferson Lewis celebrated his share of the sale of the Velvet with a sumptuous wedding feast.[146] That Olaus Jeldness would celebrate his with a party on top of Red would have been right in character. Moreover, an incident in 1904 confirmed that Olaus had made a practice of entertaining friends at celebratory "tea parties" on the top of Red Mountain. He was visiting Rossland and officiating at the ski jumping competitions in the winter carnival. After the competition, the Rossland Miner announced that

Olaus Jeldness, the first winner of the ski-running championship of British Columbia, will give one of his famous "cold tea" parties on Red Mountain on Sunday. He invites all snowshoers and ski runners to assemble on the peak of Red mountain, where refreshments will be served promptly at 2 o'clock and social exercises indulged in.[147]

Everyone "possessing snowshoes or skis" was invited. Entertainment, including "exhibitions of ski jumping," was promised. Was Olaus going to attempt some of his old ski jumping tricks? In the event, the tea party was cancelled -- or, rather, it was postponed, "to avoid a conflict with the (carnival) sports on Monte Christo Mountain."[148] There is no evidence, however, that the "postponed" party was ever held. Olaus returned to Spokane as soon as the carnival was over.

I found another story in the contemporary press of an Olaus hosted "tea party" on the top of Red Mountain in March, 1898.[149] It involved six ski club members, including Olaus, who ascended the mountain on skis to participate in a race down its face. The race had been previously announced with a starting time at "1 o'clock sharp," and many people turned out to see it. As ski club members, the six men who intended to race down the mountain were almost certainly skiers of some experience, if not great ability. When they arrived at the top they found that their lunch had been converted into a Olaus "tea party," with a meal prepared by Olaus over an open fire. The race was abandoned; the spectators who had gathered to watch another Olaus spectacular were disappointed. Clearly, the "tea" was quite strong. When they finally got around to descending the mountain, the skiers flailed about and some got lost. Injuries were incurred, but not the serious ones reported in stories of the celebratory tea party. At least two of the participants -- Thompson and Weber -- were among those reported to have been seriously wounded in the other tea party. The other three were not so named, but they could have been among the undocumented 20, all of whom were said to be injured in some degree.

Was this aborted ski race in fact the legendary "tea party," embellished by the familiar process of historical myth making? The presence of Thompson and Weber suggests that it may have been. In any case, even if it was a separate event, it was still notable, the mark of a man who embraced life to the full, who loved the outdoors and who reveled in outdoor adventures, particularly in the winter.

The "tea parties" were not the only instances of Olaus’ hi jinks on skis. On one occasion, he is reported to have skied down the face of the mountain on one long ski and one short ski to the amazement of all.[150]The standard skis of the day were very long, in the neighborhood of nine or ten feet; how short Olaus' short one was, is not reported. Skiing on one long and one short ski had a long history in old Scandinavia.[151] The underside of the short ski, called in Norwegian an "andor," was generally covered in fur, much like the "skins" of backcountry skiing today, and for the same purpose. The andor was not used for gliding, but for pushing. In effect, the skier skied only on the long ski, propelling himself on the flat or uphill by pushing with the andor in what was described as a "loping gait."[152] For downhill runs, the andor would be held above the snow's surface. In this sense, the andor substituted for modern ski poles. The ancient Norwegian skier carried only one (long) pole and it did not have a basket. It was generally not useful for propelling a skier forward but could be used for balance, as a brake and as a rudder to assist in turning. The lengths of the andor and the ski undoubtedly varied, but among the ancient Lapps it is reported that the ski was about four metres long and the andor about half that.[153] This style of skiing was taught to the Norwegian army's ski troops in the eighteenth century,[154]but by the mid-nineteenth century it had largely died out. However, in a 1900 story, attempting to explain skiing to people in Spokane, it was noted that

"In nearly all parts of Europe ... both skis are of the same length, ranging from eight to nine feet. In Finland, however, one is much longer than the other."[155]

Apparently, the technique lived on in some locations.

I don't know what Olaus was attempting to accomplish with his stunt, aside from showing off and in the process generating interest in the sport. I doubt that he was trying to introduce an ancient style of skiing to Rossland -- but it might be fun to try it.

Faced with the popularity of snowshoeing Olaus wrote a letter to the editor of the Rossland Miner -- undoubtedly tongue-in-cheek -- denigrating the other winter sport and touting the superiority of skiing over "Indian webshoes" both for transportation and for recreation "... in any kind of territory or in any country where snow falls."[156] Olaus was probably an accomplished snowshoer who had used snow shoes for transport while prospecting, but skiing was his passion. As a result of his antics, when Olaus was in town skiing received considerable attention in the press; when he was not in town, however, snowshoeing ruled the publicity roost. When Olaus left Rossland in 1899 and settled in Spokane, Washington, skiing lost its focal point and for a number of years thereafter, with a few minor exceptions, the only press attention that skiing received was at Winter Carnival time.

As a final tribute to his love of skiing and of skiing on Red Mountain in particular, in accordance with his wishes, in September, 1935, his surviving daughter and friends scattered his ashes on the top of Red.[157]

Winter Carnival [ee]

For many residents, winter in early Rossland was a dismal experience. It was cold and houses were imperfectly heated with wood burning stoves. House fires were a constant danger. Clearing of streets was limited and deep snow often blocked walking paths, making transit difficult. Some people became almost cabin-bound. Even shopping trips to town could be an ordeal. Of course, there were the usual festivities surrounding Christmas and the New Year, but the annual winter carnival, held in the dreariest month, February, was the highlight of the season.

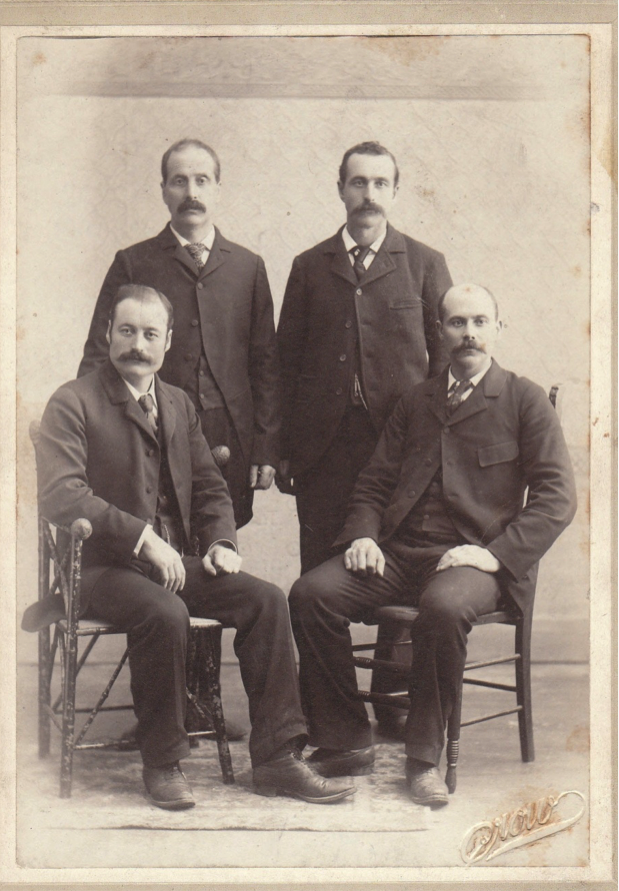

The first winter carnival was held in mid-February, 1898. Olaus is on record as claiming half the credit for originating the idea of a winter carnival, along with H.W.C. Jackson (see Annex 5, p. 106), who became the secretary of the organization.[158] That is quite plausible, and in any case the Rossland Miner thought he was of sufficient importance to the success of the venture that it noted with favour that “Olaus Jeldness is taking much interest in the proposed carnival.”[159]He was a member of the first “general committee” of 24 Rossland worthies, chaired by the mayor, that planned and promoted the event.[160] Perhaps more to the point, he was one of four on a small committee “at work on the project.”[161] He was, of course, in charge of the skiing events and to that end he planned the route of the downhill (“ski running”) event and invited skiers that he knew in Montana and Colorado to participate.[162] At least two came to town. In the days leading up to the carnival warm weather threatened both the skiing and the ice rink events. However, the day before the carnival was to open, it turned cold and began snowing. The race down Red Mountain was held as planned.[ff] At least five racers were entered and "It is thought that there will be several entries from outside town,"[163]but only three racers started, including none of the champion racers that Olaus had invited, except his brother. The race was from the top of the mountain and each racer chose his own route down. They started together and the first one crossing the finish line won. One racer broke his ski and did not finish. Olaus Jeldness came in first and his brother Anders second. It is reported that the conditions were so unfavorable that both skiers were exhausted by the race, collapsed at the finish line and immediately went home to bed.[164] The Ski jumping event was held the next day, on Spokane Street in the middle of the city to make it easy for people to watch the spectacle. The hill was reasonably steep but the run was short so long jumps were not possible. Again, Olaus won, but the length of the winning jump was not reported (it was probably embarrassingly short).[165] There were also ski races for novices and for boys.